"I can die but once."

-U.S. Grant

|

| "Angel of Death" atop the grave of U.S. Grant Jr., San Diego, CA. |

U.S. Grant's lived at a time when health care and safe working conditions were fairly primitive compared to today. It's easy to take for granted the luxury of our current medical system and forget the hardships and dangers of 19th century life. Average life expectancy was around 40 in the United States in 1850. If you add warfare to the mix, it was a very dangerous time to be alive, death was waiting around every corner. He grew up in a society that watched their loved ones die at home, the family caring for the sick or dying. Grant was not immune to the dangers of his day and faced a number of significant "brushes" with death in both civil and military life.

The first time Grant faced death that I could find reference to was a near drowning incident as a child in Ohio...

"He [Grant] enjoyed swimming in White Oak Creek, which ran just west of the town, although once he nearly lost his life when he fell off a log into the creek, then flooded as a result of recent rains, and found himself being dragged away by the current; only the alert actions of his chum, Dan Ammen, rescued him from drowning." -U.S. Grant: Triumph Over Adversity by Brooks Simpson

|

| A dangerously rain-swollen White Creek near Georgetown, OH. |

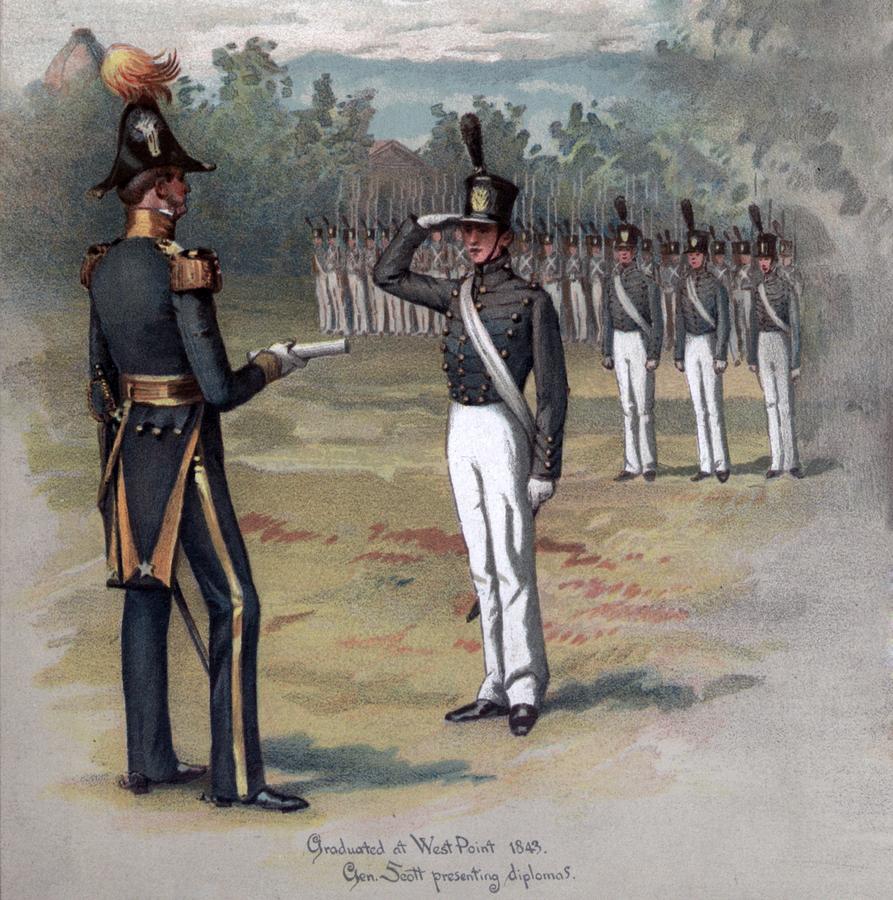

"For six months before graduation I had had a desperate cough (“Tyler’s grip” it was called), and I was very much reduced, weighing but one hundred and seventeen pounds, just my weight at entrance, though I had grown six inches in stature in the mean time. There was consumption in my father’s family, two of his brothers having died of that disease, which made my symptoms more alarming. The brother and sister next younger than myself died, during the rebellion, of the same disease, and I seemed the most promising subject for it of the three in 1843." -U.S. Grant's Personal Memoirs

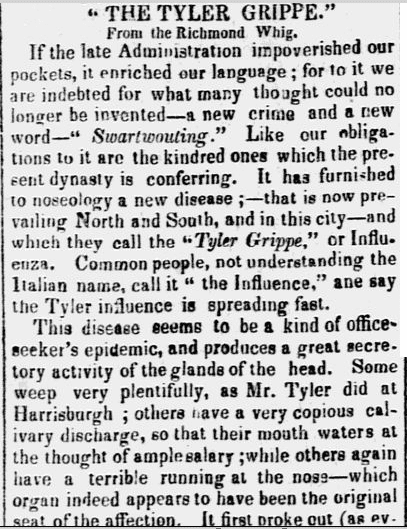

The term "Tyler's Grip or Grippe" was a reference to an epidemic of influenza which swept the U.S. during President Tyler's presidential term from 1841-1845...

"During the days when politics were real sport in the United States and political fans cared not what they called their enemies, supporters of Andrew Jackson, exhausting other epithets with which to belabor the opposition, called the flu the 'Tyler grippe'. Tyler's friends immediately responded in kind by naming the disease "Jackson's itch." -Spokane Daily Chronicle Feb 23, 1920.

|

| A newspaper reference to "The Tyler Grippe" in The Constitution (Middletown, CT), Aug. 9th, 1843. |

Influenza does not last six months, therefore in Grant's case there must have been a complication which started during the influenza period, if he even had the flu, possibly chronic bronchitis or another lung malady. Regardless of the actual cause of illness Grant does express his concern at the time regarding the possible fatal outcome of the sickness considering family history.

Grant's next period of intense mortal danger was during the Mexican War from 1846-1848. During this conflict Grant would distinguish himself by earning two citations for gallantry and one for meritorious conduct. There were multiple times that he was under fire during the conflict but a few instances of daring bravery stand out...

Grant received his first taste of warfare on May 8th, 1846 at the Battle of Palo Alto. He first heard the sounds of battle from afar, later he commented on his initial reaction, " The war had begun...for myself, a young second-lieutenant who had never heard a hostile gun before, I felt sorry that I had enlisted."

For most of the day's action they were able to avoid the bulk of the infantry and artillery fire. Towards dusk they made one last advance that proved to be the most dangerous of the day, Grant describing the casualties precariously close to him...

"One cannon ball passed through our ranks, not far from me. It took off the head of an enlisted man, and the under jaw of Captain Page of my regiment, while the splinters from the musket of the killed soldier, and his brains and bones, knocked down two or three others, including one officer, Lieutenant Wallen--hurting them more or less. Our casualties for the day were nine killed and forty-seven wounded."

|

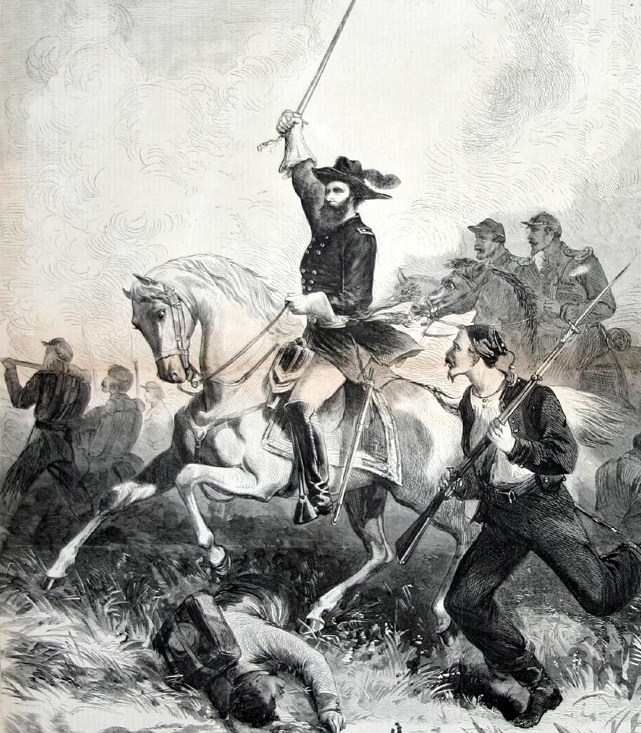

| A depiction of the Battle of Palo Alto in 1846. |

In September, 1846, during the Battle of Monterrey, Grant showcased his ability to fulfill a necessary duty regardless of the threat of personal harm. The fighting was particularly harsh during the conflict and Grant was frequently under fire with his troops, many officers were killed and wounded. At one point in the conflict while fighting in the city streets Grant illustrated a knack for ingenuity and quick thinking under pressure that would be a mark of his later military career...

"We had not occupied this position long when it was discovered that our ammunition was growing low. I volunteered to go back to the point we had started from, report our position to General Twiggs, and ask for ammunition to be forwarded. We were at this time occupying ground off from the street, in rear of the houses. My ride back was an exposed one. Before starting I adjusted myself on the side of my horse furthest from the enemy, and with only one foot holding to the cantle of the saddle, and an arm over the neck of the horse exposed, I started at full run. It was only at street crossings that my horse was under fire, but these I crossed at such a flying rate that generally I was past and under cover of the next block of houses before the enemy fired. I got out safely without a scratch." - U.S. Grant Personal Memoirs

Another particularly perilous and brave incident happened during the Battle of Molina del Rey on September 8th, 1847...

"At Molina del Rey, one of the bloodiest engagements of the war took place. The key point in the Mexican defenses was a long stone building that had been filled with Mexican infantryman. The struggle for possession of this building saw the tide of battle sweep back and forth, as the structure was captured and lost several times in fierce hand-to-hand fighting. Grant had left the relative security of his supply train during this fight and had ventured forward to the front. When he reached the scene of combat, he saw Frederick Dent lying seriously wounded on the ground, right in the middle of the contending forces, Grant rescued his future brother-in-law from the melee and saved his life." -Ulysses S. Grant: A Biography by Robert Broadwater

Grant after returning from the Mexican War, marrying his fiancee Julia Dent and being stationed in a few locations was ordered to the west coast. At the time in 1852 there was no rail travel to the west coast so they would have to take a ship to the isthmus of Panama and travel by boat, mule and train across the isthmus. This proved to be a dangerous passage and one I'm sure Grant was glad he decided to take without his new family...

“...the cholera had broken out, and men were dying every hour. To diminish the food for the disease, I permitted the company detailed with me to proceed to Panama. The captain and the doctors accompanied the men, and I was left alone with the sick and the soldiers who had families. The regiment at Panama was also affected with the disease...I was about a week at Cruces before transportation began to come in. About one-third of the people with me died, either at Cruces or on the way to Panama... we finally reached Panama. The steamer, however, could not proceed until the cholera abated, and the regiment was detained still longer. Altogether, on the Isthmus and on the Pacific side, we were delayed six weeks. About one-seventh of those who left New York harbor with the 4th infantry on the 5th of July, now lie buried on the Isthmus of Panama or on Flamingo island in Panama Bay...By the last of August the cholera had so abated that it was deemed safe to start. The disease did not break out again on the way to California, and we reached San Francisco early in September." -U.S. Grant Personal Memoirs

After resigning from the military to be reunited with his family in 1854, Grant settled down to try his hand at farming in St. Louis on the Dent's, his in-laws, property. In 1856 he built a fairly crude cabin nicknamed "Hardscrabble" and began cultivating. Around this time one of the Dent's slaves, Mary Johnson, recalled Grant had a very serious accident:

"...he came within an ace of dying. One day he was carried into the house in an unconscious condition with a fearful wound in his head. We were told that his horse had run away and thrown him, and a friend with whom he was riding, to the ground. His friend escaped uninjured, but he was so badly hurt that the attending physicians watched him closely night and day for more than a week, fearing he would not recover."

Though an accomplished horseman, Grant suffered multiple accidents while on horseback. The amount of time he spent on horseback as well as his penchant for fast and untamed horses were certainly contributing factors. His attitude relating to the dangers of horseback riding was clear at an early age. When a fellow West Point cadet, after Grant completed a set of risky horse jumps, warned him "Sam, that horse will kill you someday." Grant replied, Well, I can die but once."

It was while living at "Hardscrabble" that he suffered from Ague, which is any illness that is marked by bouts of fever and chills. His eldest son Fred Grant describes his precarious health condition amidst the struggle to keep the farm operational...

Having someone to properly care for you in those days could well be the difference between life and death. It's unknown what exactly Grant was afflicted with or for how long, but it's safe to assume that there was some concern for his long-term health and survival during this period.

"By this time the enemy discovered that we were moving upon Belmont and sent out troops to meet us. Soon after we had started in line, his skirmishers were encountered and fighting commenced. This continued, growing fiercer and fiercer, for about four hours, the enemy being forced back gradually until he was driven into his camp. Early in this engagement my horse was shot under me, but I got another from one of my staff and kept well up with the advance until the river was reached." -U.S. Grant Personal Memoirs

The Confederates drew back and the Union soldiers began to loot their camp and celebrate the victory, only to be shocked when reinforcements arrived from the other side of the river. The Union force was now surrounded and cut off from their transports on the river. Some of Grant's officers thought surrender their only option to which Grant replied that "...we had cut our way in and could cut our way out just as well..." They did fight their way to the transports, Grant being the last to leave the field in a daring bit of horsemanship under fire...

|

| A depiction of Grant's ride through the streets of Monterrey. |

|

| Fighting in the streets during the Battle of Monterrey in 1846. |

Another particularly perilous and brave incident happened during the Battle of Molina del Rey on September 8th, 1847...

"At Molina del Rey, one of the bloodiest engagements of the war took place. The key point in the Mexican defenses was a long stone building that had been filled with Mexican infantryman. The struggle for possession of this building saw the tide of battle sweep back and forth, as the structure was captured and lost several times in fierce hand-to-hand fighting. Grant had left the relative security of his supply train during this fight and had ventured forward to the front. When he reached the scene of combat, he saw Frederick Dent lying seriously wounded on the ground, right in the middle of the contending forces, Grant rescued his future brother-in-law from the melee and saved his life." -Ulysses S. Grant: A Biography by Robert Broadwater

|

| Depiction of the Battle of Molina del Rey during the Mexican-American War in 1847. |

Grant after returning from the Mexican War, marrying his fiancee Julia Dent and being stationed in a few locations was ordered to the west coast. At the time in 1852 there was no rail travel to the west coast so they would have to take a ship to the isthmus of Panama and travel by boat, mule and train across the isthmus. This proved to be a dangerous passage and one I'm sure Grant was glad he decided to take without his new family...

“...the cholera had broken out, and men were dying every hour. To diminish the food for the disease, I permitted the company detailed with me to proceed to Panama. The captain and the doctors accompanied the men, and I was left alone with the sick and the soldiers who had families. The regiment at Panama was also affected with the disease...I was about a week at Cruces before transportation began to come in. About one-third of the people with me died, either at Cruces or on the way to Panama... we finally reached Panama. The steamer, however, could not proceed until the cholera abated, and the regiment was detained still longer. Altogether, on the Isthmus and on the Pacific side, we were delayed six weeks. About one-seventh of those who left New York harbor with the 4th infantry on the 5th of July, now lie buried on the Isthmus of Panama or on Flamingo island in Panama Bay...By the last of August the cholera had so abated that it was deemed safe to start. The disease did not break out again on the way to California, and we reached San Francisco early in September." -U.S. Grant Personal Memoirs

|

| Traveling by mule across the isthmus of Panama in 1852. |

After resigning from the military to be reunited with his family in 1854, Grant settled down to try his hand at farming in St. Louis on the Dent's, his in-laws, property. In 1856 he built a fairly crude cabin nicknamed "Hardscrabble" and began cultivating. Around this time one of the Dent's slaves, Mary Johnson, recalled Grant had a very serious accident:

"...he came within an ace of dying. One day he was carried into the house in an unconscious condition with a fearful wound in his head. We were told that his horse had run away and thrown him, and a friend with whom he was riding, to the ground. His friend escaped uninjured, but he was so badly hurt that the attending physicians watched him closely night and day for more than a week, fearing he would not recover."

Though an accomplished horseman, Grant suffered multiple accidents while on horseback. The amount of time he spent on horseback as well as his penchant for fast and untamed horses were certainly contributing factors. His attitude relating to the dangers of horseback riding was clear at an early age. When a fellow West Point cadet, after Grant completed a set of risky horse jumps, warned him "Sam, that horse will kill you someday." Grant replied, Well, I can die but once."

It was while living at "Hardscrabble" that he suffered from Ague, which is any illness that is marked by bouts of fever and chills. His eldest son Fred Grant describes his precarious health condition amidst the struggle to keep the farm operational...

"I remember in those days, my father suffered very much from ague, which is a debilitating form of malaria. He would have his good days and his bad days, when he would lie in bed, shaking with the fever. My mother's care for him at such times was the soul of devotion, as it was throughout their married life." -Missouri Republican 1912

|

| "Harscrabble" cabin that U.S. Grant built in 1854 in St. Louis, MO. |

Having someone to properly care for you in those days could well be the difference between life and death. It's unknown what exactly Grant was afflicted with or for how long, but it's safe to assume that there was some concern for his long-term health and survival during this period.

As the Civil War began and Grant became heavily involved he was frequently under fire and his life in immediate danger. There are too many instances of danger to describe them all but the following are some occurrences that give a sense of what Grant faced during the war....

In November 1861 Grant, while engaged in his first action of the war at the Battle of Belmont , had some precarious moments...

The Confederates drew back and the Union soldiers began to loot their camp and celebrate the victory, only to be shocked when reinforcements arrived from the other side of the river. The Union force was now surrounded and cut off from their transports on the river. Some of Grant's officers thought surrender their only option to which Grant replied that "...we had cut our way in and could cut our way out just as well..." They did fight their way to the transports, Grant being the last to leave the field in a daring bit of horsemanship under fire...

"I was the only man of the National army between the rebels and our transports. The captain of a boat that had just pushed out but had not started, recognized me and ordered the engineer not to start the engine; he then had a plank run out for me. My horse seemed to take in the situation. There was no path down the bank and every one acquainted with the Mississippi River knows that its banks, in a natural state, do not vary at any great angle from the perpendicular. My horse put his fore feet over the bank without hesitation or urging, and with his hind feet well under him, slid down the bank and trotted aboard the boat, twelve or fifteen feet away, over a single gang plank. I dismounted and went at once to the upper deck." -U.S. Grant Personal Memoirs

On Sept. 4, 1863, while reviewing forces in New Orleans Grant had a severe equestrian accident which nearly took his life...

Near the end of his life in 1885 came Grant's final brush with death. Grant was battling throat cancer, at one point everyone thought the end had come. The Reverend baptized him, the doctors gave him shots with brandy to try to revive him, and the family braced themselves. The General recovered from this near-death experience long enough to finish his memoirs before ultimately succumbing to the illness. He said about this incident, "I was reduced almost to the point of death..."

It was his ability to let his circumstances teach him and mold him that allowed Grant to grow in from his perilous incidents. His indomitable character developed from the hardships he faced and helped others face. Reverend Charles Fowler stated that "God mixed him out of the best clay and he was improved by every successive mixing." When it was finally Grant's time to face the inevitability of a sure death he faced it with resoluteness and pragmaticism that he had developed through a lifetime of encountering and coming to terms with death. I believe Grant was never truly conquered by death because he respected and accepted it but did not not succumb to the fear of death which is what really conquers a man while he still lives.

Personal Memoirs of Ulysses S. Grant (1885)

Ulysses S. Grant by Josiah Bunting (2004)

Ulysses S. Grant, 1861-1864: His Rise from Obscurity to Military Greatness By William Farina (2007)

Meade: Victor of Gettysburg By Richard Allen Sauers (2014)

The South's Headless Hero-Terrorist, Style Weekly by Melissa Scott Sinclair, June 29, 2005.

Recollections of Corporal M. Harrison Strong, Hamlin Graland Papers, Doheny Library, University of Southern California.

Account of Grant's Military Career, Burlington Free Press by George Stannard, July 29, 1885.

General Grant's Home Life, The Independent by Frederick Grant, April 29, 1897.

Grant encountered more than a few dangerous circumstances around the time of the Battle of Shiloh in early April of 1862. The first of which involved a horse riding incident...

"On Friday the 4th, the day of Buckland’s advance, I was very much injured by my horse falling with me, and on me, while I was trying to get to the front where firing had been heard. The night was one of impenetrable darkness, with rain pouring down in torrents; nothing was visible to the eye except as revealed by the frequent flashes of lightning. Under these circumstances I had to trust to the horse, without guidance, to keep the road. On the way back to the boat my horse’s feet slipped from under him, and he fell with my leg under his body. The extreme softness of the ground, from the excessive rains of the few preceding days, no doubt saved me from a severe injury and protracted lameness. As it was, my ankle was very much injured, so much so that my boot had to be cut off. For two or three days after I was unable to walk except with crutches."

Grant, always willing to command, was even seen with a crutch strapped to his saddle during the battle. Over the course of the two days of battle Grant was on the front lines under almost constant fire. Towards the close of the first day of fighting Grant witnessed a cannonball decapitate one of his aides only yards from him. As night fell Grant, while trying to find cover, was unable to bear the scene of death and suffering he encountered:

"During the night rain fell in torrents... I made my headquarters under a tree a few hundred yards back from the river bank. My ankle was so much swollen from the fall of my horse the Friday night preceding, and the bruise was so painful, that I could get no rest... Some time after midnight, growing restive under the storm and the continuous pain, I moved back to the log-house under the bank. This had been taken as a hospital, and all night wounded men were being brought in, their wounds dressed, a leg or an arm amputated as the case might require, and everything being done to save life or alleviate suffering. The sight was more unendurable than encountering the enemy’s fire, and I returned to my tree in the rain." -U.S. Grant Personal Memoirs

He describes the similarly perilous events of the second day of fighting as well...

"In the early part of the afternoon, while riding with Colonel McPherson and Major Hawkins... suddenly a battery with musketry opened upon us from the edge of the woods on the other side of the clearing. The shells and balls whistled about our ears very fast for about a minute. I do not think it took us longer than that to get out of range and out of sight. In the sudden start we made, Major Hawkins lost his hat. He did not stop to pick it up. When we arrived at a perfectly safe position we halted to take an account of damages. McPherson's horse was panting as if ready to drop. On examination it was found that a ball had struck him forward of the flank just back of the saddle, and had gone entirely through. In a few minutes the poor beast dropped dead; he had given no sign of injury until we came to a stop. A ball had struck the metal scabbard of my sword, just below the hilt, and broken it nearly off; before the battle was over it had broken off entirely. There were three of us: one had lost a horse, killed; one a hat and one a sword-scabbard. All were thankful that it was no worse."

"On Friday the 4th, the day of Buckland’s advance, I was very much injured by my horse falling with me, and on me, while I was trying to get to the front where firing had been heard. The night was one of impenetrable darkness, with rain pouring down in torrents; nothing was visible to the eye except as revealed by the frequent flashes of lightning. Under these circumstances I had to trust to the horse, without guidance, to keep the road. On the way back to the boat my horse’s feet slipped from under him, and he fell with my leg under his body. The extreme softness of the ground, from the excessive rains of the few preceding days, no doubt saved me from a severe injury and protracted lameness. As it was, my ankle was very much injured, so much so that my boot had to be cut off. For two or three days after I was unable to walk except with crutches."

Grant, always willing to command, was even seen with a crutch strapped to his saddle during the battle. Over the course of the two days of battle Grant was on the front lines under almost constant fire. Towards the close of the first day of fighting Grant witnessed a cannonball decapitate one of his aides only yards from him. As night fell Grant, while trying to find cover, was unable to bear the scene of death and suffering he encountered:

"During the night rain fell in torrents... I made my headquarters under a tree a few hundred yards back from the river bank. My ankle was so much swollen from the fall of my horse the Friday night preceding, and the bruise was so painful, that I could get no rest... Some time after midnight, growing restive under the storm and the continuous pain, I moved back to the log-house under the bank. This had been taken as a hospital, and all night wounded men were being brought in, their wounds dressed, a leg or an arm amputated as the case might require, and everything being done to save life or alleviate suffering. The sight was more unendurable than encountering the enemy’s fire, and I returned to my tree in the rain." -U.S. Grant Personal Memoirs

He describes the similarly perilous events of the second day of fighting as well...

"In the early part of the afternoon, while riding with Colonel McPherson and Major Hawkins... suddenly a battery with musketry opened upon us from the edge of the woods on the other side of the clearing. The shells and balls whistled about our ears very fast for about a minute. I do not think it took us longer than that to get out of range and out of sight. In the sudden start we made, Major Hawkins lost his hat. He did not stop to pick it up. When we arrived at a perfectly safe position we halted to take an account of damages. McPherson's horse was panting as if ready to drop. On examination it was found that a ball had struck him forward of the flank just back of the saddle, and had gone entirely through. In a few minutes the poor beast dropped dead; he had given no sign of injury until we came to a stop. A ball had struck the metal scabbard of my sword, just below the hilt, and broken it nearly off; before the battle was over it had broken off entirely. There were three of us: one had lost a horse, killed; one a hat and one a sword-scabbard. All were thankful that it was no worse."

During the initial assaults of Vicksburg on May 22nd, 1863, Fred Grant relates a probably all too often situation for his commanding father...

"On the 22nd the great assault was made upon the fortifications. Early in the day General Grant had a narrow escape from a shell which was fired directly down a ravine which he had just entered. He was unhurt, however, but was covered with yellow dirt thrown up by the explosion." -With Grant at Vicksburg by Fred Grant

|

| General Grant at Vicksburg. |

On Sept. 4, 1863, while reviewing forces in New Orleans Grant had a severe equestrian accident which nearly took his life...

"...I went to New Orleans to confer with [Nathaniel P.]Banks about the proposed movement....During this visit I reviewed Banks’ army a short distance above Carrollton. The horse I rode was vicious and but little used, and on my return to New Orleans ran away and, shying at a locomotive in the street, fell, probably on me. I was rendered insensible, and when I regained consciousness I found myself in a hotel near by with several doctors attending me. My leg was swollen from the knee to the thigh, and the swelling, almost to the point of bursting, extended along the body up to the arm-pit. The pain was almost beyond endurance. I lay at the hotel something over a week without being able to turn myself in bed. I had a steamer stop at the nearest point possible, and was carried to it on a litter. I was then taken to Vicksburg, where I remained unable to move for some time afterwards." -U.S. Grant Personal Memoirs

An eyewitness of the incident General Lorenzo Thomas described the scene saying that Grant’s horse “threw him over with great violence. The General, who is a splendid rider, maintained his seat in the saddle, and the horse fell upon him.” Another nearby observer summed up the fears of Grant's condition at the time of the fall stating “We thought he was dead."

The incident was so severe Grant was forced to spend many weeks in Vicksburg with his family recovering and had to temporarily relinquish command to General Sherman. He was forced to use crutches for weeks, and even had to be carried on portions of the journey to Chattanooga, TN in late October. Some speculate he never fully recovered form his injuries. -Source 1 & 2

An eyewitness of the incident General Lorenzo Thomas described the scene saying that Grant’s horse “threw him over with great violence. The General, who is a splendid rider, maintained his seat in the saddle, and the horse fell upon him.” Another nearby observer summed up the fears of Grant's condition at the time of the fall stating “We thought he was dead."

The incident was so severe Grant was forced to spend many weeks in Vicksburg with his family recovering and had to temporarily relinquish command to General Sherman. He was forced to use crutches for weeks, and even had to be carried on portions of the journey to Chattanooga, TN in late October. Some speculate he never fully recovered form his injuries. -Source 1 & 2

Grant's life did not get any safer with his move to the east to take personal command of forces there. In May 1864 during the second major battle of Grant's Overland Campaign at Spotsylvania, VA, a staff member witnessed Grant's coolness under deadly fire, escaping death by the narrowest of margins:

"Grant on the battlefield I will never forget. No man was as brave, as fearless or as reckless with his life. At Spottsylvania, I was standing about 20 feet from Grant. I was looking right at him and a shell passed directly over his head. I never could believe it, but the shell passed 3 inches from his ear. He just said, 'Hudson, get that shell. Let's see what kind of ammunition they are using.' He smoked right on, and never moved a muscle and it was a six pound shell."

On August 9th, 1864 Grant was just returning to his headquarters at City Point, Virginia on the James River. City Point had become the main supply base for his campaigns against Petersburg and Richmond and therefore a strategically important spot. Grant was taking a break in the shade of a sycamore tree reading a paper at his headquarters just up the hill from the port when just after noon a huge explosion went off. A staff member described the explosion: "Such a rain of shot, shell, bullets, pieces of wood, iron bars and bolts, chains and missiles of every kind was never before witnessed." Another witnessed described the scene as "a staggering scene, a mass of overthrown buildings, their timbers tangled into almost impenetrable heaps. In the water were wrecked and sunken barges." Grant narrowly escaped being struck by shrapnel from the blast, but many others were not so fortunate. A doctor close to the scene witnessed the aftermath, a jumble of debris interspersed with the ghastly mangled human body parts. As many as 300 people were killed and wounded in the massive detonation.

The cause of the blast was much later discovered to have been a sabotage plot set forth by the Confederate Secret Service and executed by a Captain John Maxwell. He had created a "time bomb" device he called a horological torpedo which he delivered on board the JE Kendrick barge docked at City Point. The blast not only destroyed the Kendrick but also another nearby ship and resulted in an estimated two million in damages and losses. The attack although successful in it's execution did not significantly harm the northern war effort as City Point was quickly rebuilt and operational less than two weeks after the incident.

Only a month or so later in September 1864 a norwegion-born artist named Ole Peter Hansen Balling was contracted to do a painting of the General. During his visit he joined Grant on a trip to the front and described the harrowing scene that was all too commonplace for the General...

"Grant told me that Benjamin Butler commanded the right wing, then we were ashore. "Here is Deep Bottom," he said, throwing away his cigar and abruptly leaving. He jumped on shore, mounted Jeff Davis and rode off, the staff behind him. I followed, keeping as close to him as possible, often almost by his side. We went clear through the army, and came to where the bullets began. Grant waved us to stay, but we went to the edge of the woods. Here he dismounted and went into the field, where the skirmishers were rapidly firing. I could hardly breathe. We were soon in Fort Harrison, where the shells were passing and bursting. Here Grant dismounted again and seated himself at the for of an earthwork. He was immediately surrounded by the senior commanders, receiving reports and giving orders. All around us were dying men. A shell burst right over where the General sat. He did not seem to hear it."

This account also lends credence to the fact that Grant developed an almost inhuman disregard for personal danger throughout his life. Witnesses were amazed at his "nerves of steel" and his ability to stay composed in times of great excitement. I don't think this was necessarily just reckless behavior, but more so a learned trait that allowed him to function at his optimum regardless of circumstances.

Grant was again under fire at the Battle of Boydton Plank Road on October 27, 1864. While making a personal reconnaissance of Confederate forces Grant and his staff came under heavy artillery fire. Two staff members were wounded and one killed in the action. A staff officer witnessed that “Grant (who is noticeably an intrepid man) had ridden along down the road to look a little; got into a hot place, got his horse’s legs tangled in a piece of telegraph wire and ran much risk, man & horse." Grant subsequently realized the attack was futile and called it off.

The surrender of Lee and the ushering in of the end of the war did not even secure safety for Grant. In April 1865 Grant and his wife Julia were invited to join the President Lincoln and his wife at Fords Theater in Washington, DC for a play. They declined opting instead to visit family in New Jersey. Although somewhat speculative in nature, Grant was a target for assassination and probably stood a significantly higher chance for being harmed or killed if he had attended the show with Lincoln on the night he was shot by John Wilkes Booth. Grant may have dodged an assassins bullet, but Lincolns death dealt a substantial psychological blow to the General, as he respected the president greatly. "It was the darkest day of my life." Grant later told a reporter and openly wept at the slain leader's funeral.

Death was expected during war, but outside of war death could come as a surprise, occurring without warning. Grant was witness to a sad accident while boarding a train after dropping his son Fred off at West Point in March 1866. Grant's party had left a bag in the terminal and his faithful Adjutant Colonel Bowers volunteered to retrieve it. As Bowers attempted to re-enter the now moving car Grant was in, he tragically slipped and was crushed under the train. Grant was notified of the accident and solemnly replied, "'Something told me he was killed,' and viewing the mangled form of his faithful officer and beloved friend, he sadly remarked, 'That is he; a very estimable man was he. He has been with me through all my battles.'" Grant attended Bowen's funeral and appropriated money for a statue to be erected at his West Point grave.

An interesting factor in considering Grant's perilous circumstances is how often he was witness to sickness, suffering and death around him and how that affected his psyche. Many have accused Grant of being "calloused" or "indifferent" when it came to the lives of soldiers under his command. A few of his biographers have even said he had an unusual penchant for danger, drawn to war. I think these are misinterpretations of his attitude and mental state. I think being exposed to so much death and suffering throughout a military career forces you to come to terms with it and learn to process it and continue to function amidst it. I think it was this necessary coping mechanism that Grant displayed. Due to the pragmatic decisiveness that this allowed Grant was able to bring a swifter end to the Civil War. As a result many more men were saved from a slow painful death from disease than actually died on the battlefields of his final campaigns. Theodore Roosevelt added in a speech about Grant...

"At the time of the Civil War the only way to secure peace was to fight for it, and it would have been a crime against humanity to have stopped fighting before peace was conquered."

Grant definitely cared for his soldiers welfare deeply. This is displayed in his participation in numerous veterans groups and in his advocating for continued support for veterans and their families. On occasion Grant was even brought to tears as he recalled and finally came to terms with some of the tragedies of war. His son Fred explained it this way...

On August 9th, 1864 Grant was just returning to his headquarters at City Point, Virginia on the James River. City Point had become the main supply base for his campaigns against Petersburg and Richmond and therefore a strategically important spot. Grant was taking a break in the shade of a sycamore tree reading a paper at his headquarters just up the hill from the port when just after noon a huge explosion went off. A staff member described the explosion: "Such a rain of shot, shell, bullets, pieces of wood, iron bars and bolts, chains and missiles of every kind was never before witnessed." Another witnessed described the scene as "a staggering scene, a mass of overthrown buildings, their timbers tangled into almost impenetrable heaps. In the water were wrecked and sunken barges." Grant narrowly escaped being struck by shrapnel from the blast, but many others were not so fortunate. A doctor close to the scene witnessed the aftermath, a jumble of debris interspersed with the ghastly mangled human body parts. As many as 300 people were killed and wounded in the massive detonation.

|

| A depiction of the City Point, VA explosion. |

The cause of the blast was much later discovered to have been a sabotage plot set forth by the Confederate Secret Service and executed by a Captain John Maxwell. He had created a "time bomb" device he called a horological torpedo which he delivered on board the JE Kendrick barge docked at City Point. The blast not only destroyed the Kendrick but also another nearby ship and resulted in an estimated two million in damages and losses. The attack although successful in it's execution did not significantly harm the northern war effort as City Point was quickly rebuilt and operational less than two weeks after the incident.

Only a month or so later in September 1864 a norwegion-born artist named Ole Peter Hansen Balling was contracted to do a painting of the General. During his visit he joined Grant on a trip to the front and described the harrowing scene that was all too commonplace for the General...

"Grant told me that Benjamin Butler commanded the right wing, then we were ashore. "Here is Deep Bottom," he said, throwing away his cigar and abruptly leaving. He jumped on shore, mounted Jeff Davis and rode off, the staff behind him. I followed, keeping as close to him as possible, often almost by his side. We went clear through the army, and came to where the bullets began. Grant waved us to stay, but we went to the edge of the woods. Here he dismounted and went into the field, where the skirmishers were rapidly firing. I could hardly breathe. We were soon in Fort Harrison, where the shells were passing and bursting. Here Grant dismounted again and seated himself at the for of an earthwork. He was immediately surrounded by the senior commanders, receiving reports and giving orders. All around us were dying men. A shell burst right over where the General sat. He did not seem to hear it."

This account also lends credence to the fact that Grant developed an almost inhuman disregard for personal danger throughout his life. Witnesses were amazed at his "nerves of steel" and his ability to stay composed in times of great excitement. I don't think this was necessarily just reckless behavior, but more so a learned trait that allowed him to function at his optimum regardless of circumstances.

|

| Balling's painting "Grant and His Generals" |

Grant was again under fire at the Battle of Boydton Plank Road on October 27, 1864. While making a personal reconnaissance of Confederate forces Grant and his staff came under heavy artillery fire. Two staff members were wounded and one killed in the action. A staff officer witnessed that “Grant (who is noticeably an intrepid man) had ridden along down the road to look a little; got into a hot place, got his horse’s legs tangled in a piece of telegraph wire and ran much risk, man & horse." Grant subsequently realized the attack was futile and called it off.

|

| Depiction of the Battle of Boydton Plank Road, Virginia October 1864. |

The surrender of Lee and the ushering in of the end of the war did not even secure safety for Grant. In April 1865 Grant and his wife Julia were invited to join the President Lincoln and his wife at Fords Theater in Washington, DC for a play. They declined opting instead to visit family in New Jersey. Although somewhat speculative in nature, Grant was a target for assassination and probably stood a significantly higher chance for being harmed or killed if he had attended the show with Lincoln on the night he was shot by John Wilkes Booth. Grant may have dodged an assassins bullet, but Lincolns death dealt a substantial psychological blow to the General, as he respected the president greatly. "It was the darkest day of my life." Grant later told a reporter and openly wept at the slain leader's funeral.

|

| Grant and Lincoln. |

Death was expected during war, but outside of war death could come as a surprise, occurring without warning. Grant was witness to a sad accident while boarding a train after dropping his son Fred off at West Point in March 1866. Grant's party had left a bag in the terminal and his faithful Adjutant Colonel Bowers volunteered to retrieve it. As Bowers attempted to re-enter the now moving car Grant was in, he tragically slipped and was crushed under the train. Grant was notified of the accident and solemnly replied, "'Something told me he was killed,' and viewing the mangled form of his faithful officer and beloved friend, he sadly remarked, 'That is he; a very estimable man was he. He has been with me through all my battles.'" Grant attended Bowen's funeral and appropriated money for a statue to be erected at his West Point grave.

|

| U.S. Grant at Cold Harbor, VA Headquarters with Colonel Bowers (standing) and General Rawlins. |

An interesting factor in considering Grant's perilous circumstances is how often he was witness to sickness, suffering and death around him and how that affected his psyche. Many have accused Grant of being "calloused" or "indifferent" when it came to the lives of soldiers under his command. A few of his biographers have even said he had an unusual penchant for danger, drawn to war. I think these are misinterpretations of his attitude and mental state. I think being exposed to so much death and suffering throughout a military career forces you to come to terms with it and learn to process it and continue to function amidst it. I think it was this necessary coping mechanism that Grant displayed. Due to the pragmatic decisiveness that this allowed Grant was able to bring a swifter end to the Civil War. As a result many more men were saved from a slow painful death from disease than actually died on the battlefields of his final campaigns. Theodore Roosevelt added in a speech about Grant...

"At the time of the Civil War the only way to secure peace was to fight for it, and it would have been a crime against humanity to have stopped fighting before peace was conquered."

Grant definitely cared for his soldiers welfare deeply. This is displayed in his participation in numerous veterans groups and in his advocating for continued support for veterans and their families. On occasion Grant was even brought to tears as he recalled and finally came to terms with some of the tragedies of war. His son Fred explained it this way...

"Strange that to the world, General Grant could ever have seemed a 'man of iron,' and by some have been pronounced a man without a heart! We, his family, knew him to be gentle, unselfish, charitable to others, tenderhearted and always just. He often considered others and their feelings to the sacrifice of himself and his own interests....I was with my father in several great battles, and watched him during those scenes of turbulence and fearful carnage. When others became overexcited, he remained quiet, self-controlled, having on his face that set expression which enemies may have called hard and unflinching, his lips being closed firmly, with his grim determination to endure all and go through all for the final right and good. The scenes of bloodshed and agony caused him intense suffering, of which only those near him were aware." - General Grant as a Father, Youth's Companion, Jan. 19, 1899

Historian Donald Miller Grant's mindset: "In battle Grant hardly concerned himself with the issue of losses. But as even he says in, in his memoirs, when the battle was over it was very hard to take in what had happened as you walked across a battlefield filled with corpses and, and men who are still alive and barely breathing. He said, 'after the battle you begin to think about what has happened and the costs and consequences.'"

Whether he was indifferent to the danger of strangers, Grant apparently developed a lack of concern for his own welfare when engaged in duty. His Civil War staff member and friend Adam Badeau described Grant's relationship with mortal danger:

“[Grant] never braved danger unnecessarily; he was not excited by it, but simply indifferent to it. I have seen him sit erect in his saddle when everyone else instinctively shrank as a shell burst in the neighborhood.” “Ulysses don’t scare worth a damn.”

Similarly General Horace Porter recalled:

"General Grant was the only man I ever saw...who could go through a battle without flinching. He never lacked in courage, never dodged. He wouldn't as much wink when bullets went whizzing by. He had iron nerves. He was never hurt by a bullet, despite his exposure...”

John Young, a journalist who traveled with Grant on his world tour, explained the General's unflinching bravery:

"He had perfect courage, and although answering that he never went into a battle without fear, or left it without joy, the evidence goes to show that his courage in battle was serene. It was the courage of an absorbed, intensely concentrated soldier doing his duty. He had perfect faith, not alone in the righteousness of his cause, but in its triumph."

And General George Stannard commented on his demeanor when facing deadly circumstances:

"When under fire, the General never gave, as I've said, any indication that he was thinking of the bullets. He went where his duty took him, regardless of the sometimes extreme danger. He always seemed to drop himself out of his consciousness in his devotion to the special work that had fallen upon him."

These accounts all seem to agree that Grant had the ability to ignore danger when wholly consumed with the completion of his duty. It could be said that Grant should not have been so reckless, but I think the places Grant went were places he carefully reasoned were necessary for him to be in order to fulfill his assignments. In the end he was not willing to let anything, not even immediate danger, get in the way of him completing his duties.

Ferdinand Ward was Grant's wall street partner who turned out to be a crook who was responsible for financial ruin late in his life. Ward recalled a potentially fatal incident involving Grant at their offices in New York City in the early 1880's:

"A few minutes after he [Grant] arrived one of the officers of a bank which was located in the same building came running into the office. His face was pale, and with the greatest concern he inquired of the General if the latter was all right, to which General Grant replied in the affirmative in an unconcerned way. I was greatly surprised at the scene and asked what it meant. The General laughed and said he supposed his friend from down stairs referred to an incident which he had already forgotten. 'As I was coming up in the elevator this morning the rope parted,' said the General, 'and we fell several floors. Fortunately the automatic brake worked and we got nothing worse than a shaking up. All in all, it was a rather interesting experience.' That was all. He regarded his escape from death as something too trivial to mention when he came into the office."

“[Grant] never braved danger unnecessarily; he was not excited by it, but simply indifferent to it. I have seen him sit erect in his saddle when everyone else instinctively shrank as a shell burst in the neighborhood.” “Ulysses don’t scare worth a damn.”

Similarly General Horace Porter recalled:

"General Grant was the only man I ever saw...who could go through a battle without flinching. He never lacked in courage, never dodged. He wouldn't as much wink when bullets went whizzing by. He had iron nerves. He was never hurt by a bullet, despite his exposure...”

John Young, a journalist who traveled with Grant on his world tour, explained the General's unflinching bravery:

"He had perfect courage, and although answering that he never went into a battle without fear, or left it without joy, the evidence goes to show that his courage in battle was serene. It was the courage of an absorbed, intensely concentrated soldier doing his duty. He had perfect faith, not alone in the righteousness of his cause, but in its triumph."

And General George Stannard commented on his demeanor when facing deadly circumstances:

"When under fire, the General never gave, as I've said, any indication that he was thinking of the bullets. He went where his duty took him, regardless of the sometimes extreme danger. He always seemed to drop himself out of his consciousness in his devotion to the special work that had fallen upon him."

These accounts all seem to agree that Grant had the ability to ignore danger when wholly consumed with the completion of his duty. It could be said that Grant should not have been so reckless, but I think the places Grant went were places he carefully reasoned were necessary for him to be in order to fulfill his assignments. In the end he was not willing to let anything, not even immediate danger, get in the way of him completing his duties.

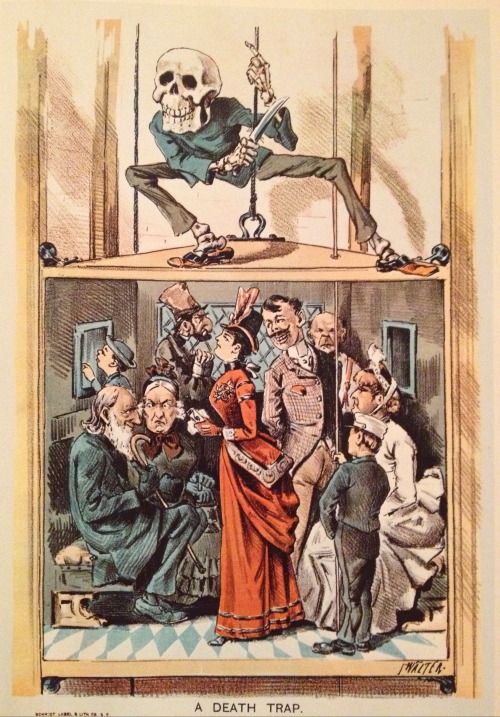

Ferdinand Ward was Grant's wall street partner who turned out to be a crook who was responsible for financial ruin late in his life. Ward recalled a potentially fatal incident involving Grant at their offices in New York City in the early 1880's:

"A few minutes after he [Grant] arrived one of the officers of a bank which was located in the same building came running into the office. His face was pale, and with the greatest concern he inquired of the General if the latter was all right, to which General Grant replied in the affirmative in an unconcerned way. I was greatly surprised at the scene and asked what it meant. The General laughed and said he supposed his friend from down stairs referred to an incident which he had already forgotten. 'As I was coming up in the elevator this morning the rope parted,' said the General, 'and we fell several floors. Fortunately the automatic brake worked and we got nothing worse than a shaking up. All in all, it was a rather interesting experience.' That was all. He regarded his escape from death as something too trivial to mention when he came into the office."

|

| An 1880's cartoon showing the danger of elevator use. |

Near the end of his life in 1885 came Grant's final brush with death. Grant was battling throat cancer, at one point everyone thought the end had come. The Reverend baptized him, the doctors gave him shots with brandy to try to revive him, and the family braced themselves. The General recovered from this near-death experience long enough to finish his memoirs before ultimately succumbing to the illness. He said about this incident, "I was reduced almost to the point of death..."

.jpg) |

| Grant attended by his doctors during his final illness. |

It was his ability to let his circumstances teach him and mold him that allowed Grant to grow in from his perilous incidents. His indomitable character developed from the hardships he faced and helped others face. Reverend Charles Fowler stated that "God mixed him out of the best clay and he was improved by every successive mixing." When it was finally Grant's time to face the inevitability of a sure death he faced it with resoluteness and pragmaticism that he had developed through a lifetime of encountering and coming to terms with death. I believe Grant was never truly conquered by death because he respected and accepted it but did not not succumb to the fear of death which is what really conquers a man while he still lives.

Sources:

Personal Memoirs of Ulysses S. Grant (1885)

Ulysses S. Grant by Josiah Bunting (2004)

Ulysses S. Grant, 1861-1864: His Rise from Obscurity to Military Greatness By William Farina (2007)

Meade: Victor of Gettysburg By Richard Allen Sauers (2014)

The City Point Explosion from Petersburg by Bruce Brager (2003)

Colonel Theodore S. Bowers, Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society by Theodore G. Risley October 1919.

Why Shiloh Matters, The New York Times by Winston Groom, April 6, 2012.

"Great Many Damned Fools in This Army" - Battle of Burgess' Mill, Civil War Daily Gazette October 27, 2014.

Mary Johnson Interview, St. Louis Republican, July 24, 1885.

Patriotic Orations by Charles Henry Fowler, 1910.

General Grant As I Knew Him, New York Herald by Ferdinand Ward, December 19, 1909.

Why Shiloh Matters, The New York Times by Winston Groom, April 6, 2012.

"Great Many Damned Fools in This Army" - Battle of Burgess' Mill, Civil War Daily Gazette October 27, 2014.

Mary Johnson Interview, St. Louis Republican, July 24, 1885.

Patriotic Orations by Charles Henry Fowler, 1910.

General Grant As I Knew Him, New York Herald by Ferdinand Ward, December 19, 1909.

Recollections of Corporal M. Harrison Strong, Hamlin Graland Papers, Doheny Library, University of Southern California.

Account of Grant's Military Career, Burlington Free Press by George Stannard, July 29, 1885.

General Grant's Home Life, The Independent by Frederick Grant, April 29, 1897.

.jpg)