"...to get clear of guerrillas...a certain time be given for them to come in... after which they will be proceeded against as outlaws."

-US Grant

|

| Confederate John S Mosby on a train raid. |

On a day in mid March 1864 a small skirmish occurred near Estill Springs, TN which owing to it's scale and timing is now only a forgotten footnote in Civil War history. If the timing was just a little different the whole end of the war may have been substantially altered.

|

| US Grant receives his commission as Lieutenant General from President Lincoln. |

On March 9th Grant was in Washington DC at the White House receiving a commission for Leuitenant General from President Lincoln. He then traveled back to Nashville, TN and arrived by the 14th to make arrangements to leave the west and assume personal command of the armies of the eastern theater. One thing did not change however, he was reliant on rail travel, in fact moreso the higher he rose in rank and responsibility.

|

| US Grant's Lieutenant General Commission dated March 10th, 1864. |

Due to the volatile nature of the border states and their split allegiances this area spawned some of the most prolific and infamous guerrilla bands both Union and Confederate. Some even theorize that the predominant Scotch-Irish heritage of the area contributed to the proliferation of guerrillas due to the deep-rooted traits such as mistrust of authority, kin loyalty and violent feuds brought over by the original settlers. Some of the names of southern guerrilla leaders such as "Bloody Bill" Anderson, Quantrill and his Raiders and the infamous 'Gray Ghost" John Mosby are well known. These so called "Partisan Rangers" were recognized to different extents by the Confederate government and the groups were not generally known for following official army organization or protocol. They were some of the most feared men because of their unpredictable behavior and uncouth tactics. Every private on the picket line was wary of the possibility of a guerrilla attack on their post at any moment. Even northern sympathizing civilians and "contraband" blacks were targets of these outfits that did not always fight under the standard "rules of engagement" for warfare. Due to their conduct they were typically not perceived as military combatants but outlaws by the opposing force. When the war was over they were often the last to be rounded up for surrender, some choosing instead to disband their units. However one lesser known guerrilla leader's heinous reputation secured for him a more unique fate.

|

| Champ Ferguson in 1865. |

Samuel "Champ" Ferguson was born in Kentucky in 1821 and moved to the Calfkiller River Valley near Sparta, TN with his wife at the outbreak of the war. He is said to have exhibited a violent nature throughout his life. When the war broke out it was claimed that he chose the Confederate side for reasons related to past offences, but it was a deeply divided state and his own brother even joined the Union army. His animosity for Yankees and those he branded as personal enemies was evident in his violent and merciless action towards them.

|

| Calfkiller River, Tennessee. |

During the early part of the war Ferguson conducted raids with his band of raiders and Sparta, TN became a home-base for guerrilla operations in the area of the Cumberland Plateau. The mountainous area had a "wild-west" character to it and was perfect for the elusive bands to stay hidden and receive aid from sympathetic locals. Ferguson and his men joined forces at times with others such as Mosby. The Union army took the threat of these raiders seriously as they could substantially disrupt operations and were erratic and hard to combat. Gen. U.S. Grant sent out a letter requesting the refitted 5th TN Cavalry (Union) under the command of Col. William B Stokes to be "sent immediately to clear out the country between Carthage & Sparta of guerrillas." Stokes, a former Tennessee Congressman, had somewhat limited success in his assignment, due to the difficult nature of fighting guerrillas, but his presence was nonetheless a statement that the activity would not be tolerated.

|

Col. William B. Stokes, tasked with fighting the Confederate guerrillas.

|

The threat of increased Union action led to the consolidating of various Confederate guerrilla forces in the area. This included a Col. John M. Hughs (also Hughes) of the 25th TN Infantry (Confederate) who had been assigned to round up deserters and enforce conscript laws. Hughs and his mounted detail found themselves trapped in enemy territory so they began teaming up with other "irregular" units in the area and harassing the Union war effort.

|

| Sergeant James Griffith, a soldier who fought guerrillas in Stokes' 5th TN Cavalry. |

On the 11th of March Ferguson, along with Hughs, engaged in a skirmish with Stokes along the Calfkiller River. During the engagement Ferguson was severely wounded and hid to avoid capture and, he believed, certain execution. Ferguson continued to hide out for the next couple months recovering from his wound. During his absence it appears at least some of the force continued operations under the command of Hughs.

|

| Civil War era map showing the N&C Railroad through Tallahoma and Estill Springs, TN. |

The area of East Tennessee was a volatile mix of secret aiding, abetting and bitter feuds. The 27th Indiana Infantry who had recently come back into service through reenlistment, was stationed in Tullahoma, TN (near Estill Springs) in the winter of 1863-64. Edmund R. Brown in his regimental history of the 27th IN describes the dangerous atmosphere that pervaded the area...

"...the people... to the east and north, were quite generally loyal. At least, there were enough in those section that were loyal to make it too hazardous for bushwackers. But not far south, and southwest, was a section of country where the rebel sentiment was rampant...The people in the above direction from Tullahoma encouraged guerrilla warfare and bushwacking, harboring and assisting in hiding those engaged in it."

|

27th Indiana Infantry who were stationed in the guerrilla-filled region of Tullahoma, TN.

|

Brown then relates the murder of three prisoners by some of the guerrillas in the area. In response to this atrocity Gen. George Thomas, commander of the Army of the Cumberland, issued an order for rebel citizens in the area of the incident to contribute to a sum of $30,000 to be sent to the widows and families of the victims. This fully illustrates the complicated task of conducting reasonable military rule in an area such as this.

Brown goes on to talk about the frequent raids on the railroad line near Tullahoma, how the guerrillas used the terrain and cover in the area to their advantage and how they evaded capture...

"Below Tullahoma some distance the railroad passed through a thinly settled, wooded country...a region of deep ravines and steep, rocky hills, all thickly covered with trees and bushes. This region furnished the marauders a vantage ground, from which to sally out and to which to retreat. Their attacks upon the railroad were always late in the afternoon, and before they could be pursued far, darkness would come to their aid. By morning they would be dispersed, and in appearance, and by profession, they would be the most harmless and inoffensive of citizens."

It is this nature of melting back into the general populous that still makes warfare so complicated, unable to tell combatants from non-combatants. To scrupulous military men this behavior was despicable but proved very difficult to stop.

|

Workers repairing the N&C Railroad in 1863.

|

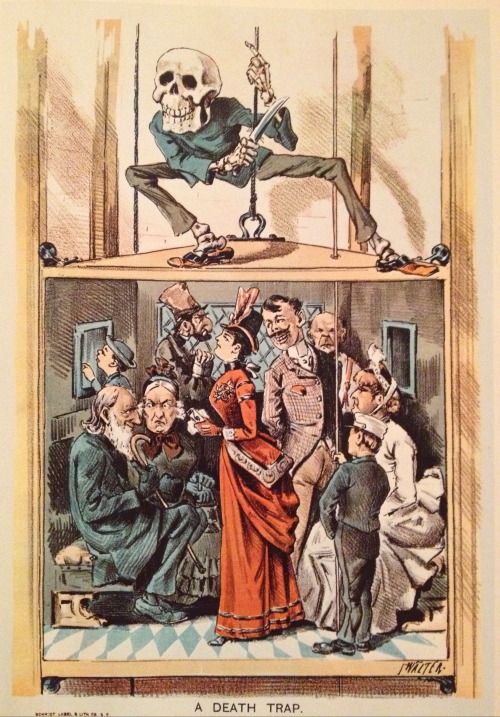

Railroad raids were common on both sides of the war. It was a sure way to disrupt the movement and supply of an opposing enemy, and confiscate, or destroy, large quantities of goods and take prisoners.

On March 16th, 1864 not far from Tullahoma, a skirmish occurred along the Nashville & Chattanooga railroad line near Estill Springs, TN. The accounts of the railroad raid and subsequent skirmish between "Ferguson's Guerrillas" under Col. Hughs and members of the 123rd NY Infantry vary somewhat so I will provide a few first-hand and second-hand reports on the raid from both sides...

Corporal Henry Welch of Co K, 123rd NY wrote to his mother the day before the skirmish, showing a somewhat ominous optimism about the risk of guerrillas...

.jpg) |

| Corporal Welch's letter to his mother written the day before the skirmish. |

"...we are out scouting over the country a good deal. Two of us took our guns and went six miles back the other day, we had a good time. I have not seen a guerilla since we came out here. I think they are scarce. We move about one mile every day. So you see that we do not lay still long at a time. I am going to Tullahoma today as train guard. I will mail this letter at that place."

Corp. Welch must have been either brave, foolhardy, restless or a combination of all three, for only nine days after the skirmish he wrote home to his father telling him"...I came pretty near getting in a scrape last night." He goes on to write about going out, surprisingly, alone in the woods for a stroll with his rifle, then coming upon turkeys and stalking them until he was lost. He finally came to a home and asked for directions because he "...knew there was now and then a bushwacker [guerrilla] about so I must find my way back to camp if possible." He went back out in the rainy dark night and ended up back at the same house two hours later! The owner of the home seemed suspicious so Welch told the man to guide him back to camp. They reached camp near midnight and the men had feared him dead. He wrote that he would not tell his fellow soldiers about making the man guide him.

|

Corp. Henry Welch Co. K 123rd NY

|

The official report from Capt. George Hall of Co. E 123rd NY is the most comprehensive account....

"I have the honor to report that yesterday (16th) at 1 p. m. I received intelligence of a citizen by the name of Martin Hays, sent by citizen named John P. Hefner, who tends a grist-mill about 2 miles from this post, that a band of rebel cavalry from 70 to 100 and Chattanooga Railroad, and said they were going to throw off the first train of cars from Tullahoma and then blow up the bridge across Elk River. On receiving this intelligence, I immediately reported it to Maj. Tanner, commanding One hundred and twenty-third Regt. New York Volunteers, and reinforced my pickets accordingly, and awaited orders from the major; but receiving no definite orders and awaiting sufficient time for my patrols to return, not having sufficient force here to leave the stockade safe and meet the enemy, I took the engine of the construction train, which was here, and went to the regiment and reported the facts to the major, who immediately sent Company C to take the place of my company (E) and sent my company in pursuit of the enemy.

At 4.45 p. m. I left camp, marching with the main part of my company on the railroad, having a line of skirmishers on each side of the road a reasonable distance in advance. After proceeding nearly 11/2 miles I saw a train coming from Tullahoma, and watched in until it ran off the track, and heard the firing on the train. It was about one-half mile in advance of my skirmishers. I then filed to the right into the woods and took the double-quick step in order to flank them, but they had got notice of my approach and commenced a retreat. I came up on their flank, opening upon them, which was returned by them, but made no stand of any account; formed line of battle twice, but as soon as we fired upon them they turned and ran. I pursued them about 11/2 miles, when my men became so much exhausted that farther pursuit would have been useless and I returned to the wreck, where I found the cars on fire, but succeeded in extinguishing the fire so that but three cars were burned. The engine was but little injured.

During the fighting, men captured from the cars were recaptured, and in about one hour the remainder of the prisoners came in-7 of the Twenty-seventh Indiana and 2 men of Company E, One hundred and twenty-third New York Volunteers; also Capt. Beardsley, of the Twentieth Connecticut, and Lieut. Williams. All were robbed of everything valuable, not excepting their clothing. Two men of the First Michigan Engineers were wounded; also a citizen by the name of Stockwell-the latter seriously, the ball having passed through the left lung. One negro was killed and 1 wounded. The prisoners report that the rebels were commanded by Lieut.-Col. Hughs, formerly of the Twenty-fifth Tennessee. The names of the other officers I could not learn. One of my company that is reliable told me that he counted 97 men, while a prisoner, and at the time 15 or 20 were out after the other patrols. The man spoken of above of my company was one of the patrols who were captured. They were armed with carbines and rifles. The last I heard of them they passed the mill about 2 miles from here at dark, apparently in great haste. Two of their men were killed, and 1 seriously wounded. I captured three saddles and one carbine. Had I been a few minutes earlier I could have saved the train, and think killed or captured most of them."

Hall later recounted the incident slightly differently for pension paperwork in 1897...

|

| Captain George R. Hall Co. E 123rd NY |

|

|

|

|

First Lieutenant Robert Cruikshank of Co. H, 123rd NY described the incident in a letter to his wife...

"Captain George R. Hall had an exciting time with a band of guerrillas numbering one hundred and twenty on the 16th inst. The patrol not returning on time to Estell Springs where the Captain and his Company (E) are stationed, he took forty of his men and started out to see what had become of them. When about three miles up the track he saw that a band of guerrillas had wrecked a train and was burning it and robbing the passengers. The Captain charged his company on them at once, retaking the patrol and other soldiers who were on the train whom the guerrillas had taken as prisoners. He then flagged two other trains that were following the one that was wrecked. On this road that is the way they run the trains,- three, one after the other. The guerrillas charged on Company E, but they beat them off, killing two. The Captain and his forty men saved several men from being taken prisoners, three engines, sixty cars DO loaded with supplies, and perhaps General Grant as he was in the second train. Geo. H. Edie of our Company was on the first train when wrecked and he lost five dollars in money, a watch, and would have lost his overcoat had not Company E come up when they did. They left him taking it off.

You can see what sort of men the 123rd Regt. are made of, to attack three of the enemy to one of their number and put them to flight. We have a brave lot of fellows that I believe enjoy such a skirmish. It breaks the monotony of camp life and gives them something to talk about and something to write about.

With love,

R. Cruikshank."

First Lieutenant Robert Cruikshank and a portrait of his wife and daughter.

Since it was a bloodless assault by the men of the 123rd, Cruikshank took the liberty to say that the boys even enjoyed the action and it helped break up the boredom of camp life. Regardless of this "enjoyable" excitement it must have also served to put the whole regiment on watch for further attacks. He also shares the unsubstantiated claim that Gen. Grant was on one of the trains enroute to the skirmish location.

In his 1879 regimental history Sgt. Henry C. Morhous of Co. C 123rd NY recounted the event as follows...

"On the 16th of March Co. E had a sharp skirmish with Ferguson's guerillas. On the day named, Capt. Geo, R. Hall had sent out two men and a Corporal to patrol the road half way between his post and Tallahoma. Ransom Qua and Chauncey P. Coy, we think, were two of them. The patrol not returning at the regular time, the Captain at once made up his mind that "something was up.'" He accordingly got out his company, and had proceeded up the track about one mile when he came in sight of the guerillas. The latter had run a train off the track and had fired three cars of hay. On the train were several soldiers, three of them from the Regiment. When Co. E came in sight the guerillas were relieving the boys of their overcoats, money, watches, etc. Co. E charged on them, driving them and retaking the prisoners. After driving them for nearly a mile the Rebels came up with another squad of their men who had been dispatched for some purpose, when they turned upon Co. E, driving them for some distance. Capt. Hall rallied his men and once more drove the enemy. This time they did not come back. The captain pursued them for some distance, but he found it useless as the Rebels were mounted. Sergeant G. Stevenson of Co. G, had about $20 taken from him, besides his overcoat. Private W. Arnold ofthe same company also had some money taken from him. Arnold had Lieut. Hills watch, but when they asked him if he owned a watch he told them no and succeeded in concealing it from them. Private George WEdie of Co. H had his watch and about $5 taken. They told him to pull off his overcoat, but Co. E coming in sight just then they did not wait to get it. The guerillas shot one negro who was braking on the train. Co. E killed two of the guerillas, but none of the boys in the company were hurt. The guerillas numbered 120, while the Captain had but 46 men. By the bravery of Capt. Hall and his little band, three engines and at least sixty cars loaded with supplies for the army at Chattanooga, were saved. They used to run three trains, one right after the other, and had Co. E not appeared on the scene the guerilla would not only have destroyed this large train, but the two which followed, and they might also have captured Gen. Grant, for he was on the second train. Great praise was due Capt. Hall for his promptness and judgment, and to his companv for the brave manner in which they conducted themselves. But we suppose no soldiers were ever more pleased to see their company than were these same boys who had beentaken prisoners by the guerillas, and who were being robbed of all they had."

|

| Seargent Henry C. Morhous, author of the 123rd Regimental history. |

Col Hughes, the only Confederate report of the incident that could be found, does not seem to completely agree with the Union accounts...

"On the 18th [16th] March we tore up the Nashville and Chattanooga Railroad near Tullahoma and captured a train of freight cars heavily laden with supplies for the Federal army at Chattanooga. About 60 Yankee soldiers were captured and about 20 Yankee negroes killed. The train and supplies were burned."

|

| Col. John M. Hughs, Confederate raider |

Both a local newspaper and the newspaper from the 123rd NY's home area both ran accounts of the skirmish...

From the Nashville Dispatch, March 18, 1864...

"Railroad Raid"

"Some Confederate cavalry made a raid on the Nashville and Chattanooga railroad, on Wednesday evening, in the neighborhood of Estelle Springs. There are numerous stories floating about town on the subject, of which this is one: That on Wednesday a body of Confederate cavalry, under Col. Roddy [Correction - Other sources cite Col. John M. Hughs as commander], arrived in the neighborhood above indicated, and throwing out his pickets, tore up a portion of the track; his men then concealed themselves, and the up-train came thundering along, with three other trains close up. The first soon became a wreck, the second ran into the first, and the third into the second, before they could be stopped; the confederates in the meantime coming out, firing into the train guard, and capturing a few of them. The engineer of the fourth train "smelt a mice," and put back, while the Confed's burned the three trains, destroyed the Elk river bridge, and put as if the devil had been after them. A correspondent of the Louisville Journal tells the story thus, in a telegram from Decherd, dated the 16th: 'A band of guerrillas under Colonel (unknown,) attacked the freight train from Nashville, near Estelle Springs tonight. By displacing a rail the train was thrown off the track and burned. Capt. Beardsley of the 123d New York [Correction - Capt. Ambrose E. Beardsley was from the 20th CT/Brigade Inspector] and seven men have just arrived here on a hand car, having been paroled after being stripped of their clothing and money, watches and jewelry. The Rebels killed three negroes who were on the train. Two of the band were killed. No losses on our side. They belonged to Roddy's command.'"

A letter from a 123rd NY Soldier published in the Whitehall Chronicle on April 1st, 1864...

"BRO HENRY:

Last Thursday, about 5 o'clock, our company was called upon to go and relieve company E, which was stationed at the Water Tank about a mile up the track; to go in search of some of their boys who went out on patrol at 1 o'clock, and had not returned. At half past 5 we had relieved them, and they (Co. E) had just thrown out a few skirmishers to feel along the road to see whether there were any of the enemy concealed; but not finding any, they pushed on farther without seeing any signs of the enemy. They had not proceeded a great distance when a volley of musketry was heard not very far in advance. The Capt. then ordered the company to double-quick; they did so, and in a few moments they reached the scene of excitement, which was caused by 150 Rebel cavalry, who had run the train off, burnt three cars, shot two negroes, and an engineer who was shot through the thigh. A quartermaster was robbed of $600, and a Captain of a Conn. Regiment of $300. There were a number of company G boys who were returning from Tullahoma on the same train; their overcoats were taken including their money and jack-knives; and also relieved the patrol of their overcoats and money, and were in the act of taking them to the rear, when company E came up with a yell, and one volley caused the "Rebs" to retreat in hot haste, killing two and wounding one; not one of company E were hurt. No more news at present. Everything is all quiet along the road.

Your brother,

CHARLIE."

Though the March 16th skirmish did not go down in history as a decisive engagement, the quick actions of Capt. Hall and Co. E of the 123rd NY certainly averted further death and damage. It also marked the beginning of the end for Col. Hughs guerrilla operations. He was pursued and chased out of the area by some of Col. Stokes men over the next few days. He would return through enemy lines and rejoin the main Confederate force in April.

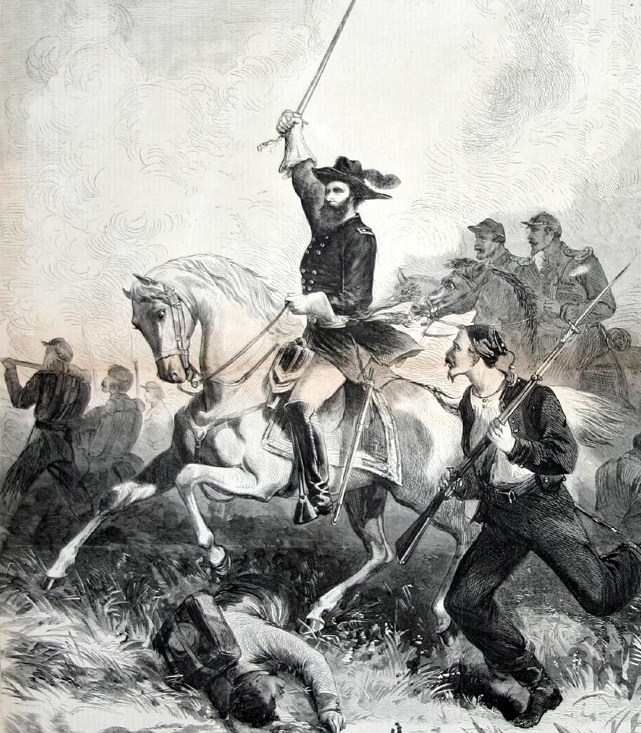

Was General Grant really on one of the trains that day? I could not find any evidence that he was. During the time in question he was sending telegraphs from Nashville. In a telegraph on the 14th Grant states "I shall leave here about the last of the week." On the 16th at 7PM, after receiving reports of possible enemy action, he sends a message to Gen. Thomas ordering him to"...place heavy guards upon the important railroad bridges both East and West of Chattanooga..." Sherman arrived to assume command on the 17th. On the 18th Grant accepted a ceremonial sword from the citizens of Joe Daviess County Ill., made a speech and boarded a train for Washington DC. Whether it was a couple hours or days, it seems as though this still illustrates the constant threat that guerrillas posed during the war. They were unpredictable wild-cards in an otherwise orchestrated game of chess.

To further illustrate the danger of wartime travel, on April 15th Grant had an even closer call as Confederate geurrillas under John Mosby attacked near Bristoe Station, VA only a short time after his train passed through. Small bands of raiders did frequently succeed in taking prisoners, including high ranking officers, throughout the war making Grant's capture a distinct possibility.

|

| A train derailed by Confederate cavalry shows the dangers of wartime rail travel. |

After years of reports of cruelty and disruptiveness of guerrilla outfits Gen Grant was unwilling to treat unidentifiable "raiders" as anything but common outlaws. He sent word to Gen. Philip Sheridan in 1864 on how to deal with Mosby's Rangers...

"The families of most of Moseby's men are know[n] and can be collected. I think they should be taken and kept at Fort McHenry or some secure place as hostages for good conduct of Mosby and his men. When any of them are caught with nothing to designate what they are hang them without trial."

In an ironic turn Mosby actually later became a republican, supported Grant for president and became well acquainted with him. Grant even commented in his Memoirs...

"Since the close of the war, I have come to know Colonel Mosby personally and somewhat intimately. He is a different man entirely from what I supposed. He is able and thoroughly honest and truthful."

|

| John S. Mosby c.1880. |

As the war drew to a close Grant set an ultimatum for the surrender of guerrillas on May 5th 1865...

"I would advise as a cheap way to get clear of guerrillas that a certain time be

given for them to come in, say the 20th of this month, up to which time their

paroles will be received, but after which they will be proceeded against as

outlaws.

U. S. GRANT, Lieut.-Gen."

Col. Hughs, himself rumored to have committed heinous war-crimes, resigned his commission shortly before the war ended and faded into obscurity, dying years later in Tennessee.

Champ Ferguson eventually returned to his guerrillas and continued to harass the Union army until the end of the war. He was captured at his home and stood trial for war crimes. The trial was widely publicized and he was convicted of 53 murders and sentenced to hang. Ferguson, perhaps in a fitting statement, was escorted to the gallows by a unit of US Colored Troops. His response to his verdict was to justify his actions as acts of self-defense and was indicative of the defiant nature shared by many guerrillas...

"I am yet and will die a Rebel … I killed a good many men, of course, but I never killed a man who I did not know was seeking my life. … I had always heard that the Federals would not take me prisoner, but would shoot me down wherever they found me. That is what made me kill more than I otherwise would have done. I repeat that I die a Rebel out and out, and my last request is that my body be removed to White County, Tennessee, and be buried in good Rebel soil."

The accusations against him of brutality and cold-blooded murder are still debated and he remains one of only two (the other being Henry Wirz commander at Andersonville Prison Camp) to be executed for war crimes after the Civil War.

|

| Execution of Champ Ferguson from Harper's Weekly 1865. |

Guerrilla warfare still holds a negative connotation for many who respect the rules of engagement. For others their vigilante style is romanticized and justified. Some former Confederate guerillas joined together after the war to form infamous outlaw bands, such as the James-Younger Gang, unwilling to relinquish the lifestyle. The controversy over Ferguson continues as with many of the men embroiled in the desperate and trying conflict. To some he is seen as a folk hero, to others a terrorist...

The 123rd NYSV were recruited from Washington County, New York in 1862 and had a storied three years of service. They fought in major battles of the east such as Chancellorsville and Gettysburg, and after transfer west took part in the campaign for Atlanta and Sherman's "March to the Sea".

|

| 123rd NY Veterans at the 1888 monument dedication at Gettysburg, PA. |

Note: For those interested Hartford N.Y. boasts one of the few remaining civil war enlistment centers, showcasing artifacts and material relating to the 123rd NYSV.

|

| Civil War Enlistment Center Hartford, NY. |

For further research on the 123rd NYSV:

For further research on East Tennessee in the Civil War:

.jpg)

.jpg)